By Gabriel Azicate

October has been designated as Black History Month in the UK as a way of celebrating the contributions of the Afro-Carribean community to British history. Established in 1987, this celebration now extends to Asian and minority ethnic groups as well.

Tinig UK would like to mark this important occasion by sharing this piece on British-Philipppine relations written by Gabriel Azicate. He wrote this piece when he was in Year 9 at Loreto High School in Manchester. He is currently a second year student in the University of Sheffield studying Modern Foreign Languages and Cultures.

It all started when I mentioned to my dad that we were studying the Seven Years War in our history class. He said casually, “Oh that was when the British occupied Manila in 1762.”

I did not know that, and as we talked more on the history of the Philippines, I learned that there were many instances when British and Philippine history intersected. The more we talked about it, the more it seemed interesting. So this is where my story begins…

It starts with trade

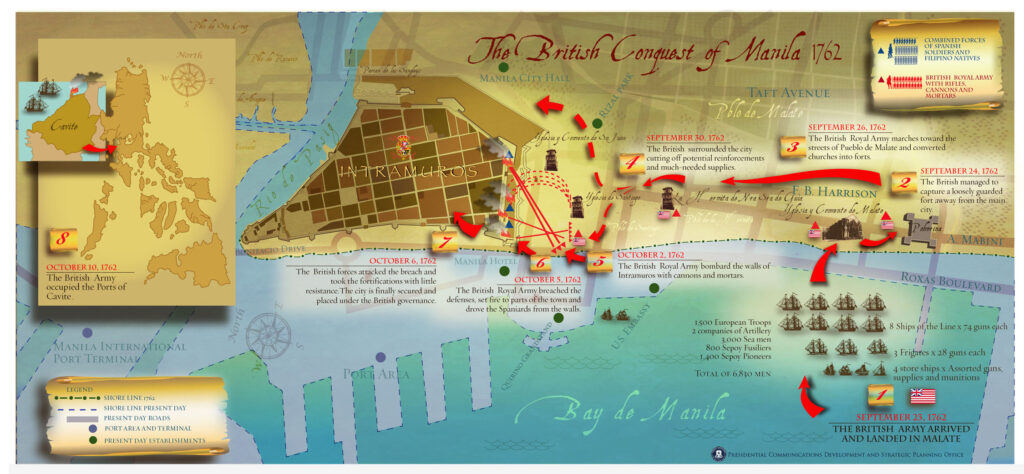

Actually, it was the forces of the British East India Company that besieged and occupied Manila. The city was sacked and plundered after it was surrendered. Many of the treasures from Manila eventually turned up in Britain. A good example is one of the first books printed in the Philippines, Doctrina Christiana.

This event had important effects on Filipinos. Some decided to continue supporting the Spanish. The resistance of the Spanish and Filipino forces outside Manila prevented the British from expanding the territory they controlled beyond the area around walled city of Manila or as the Spanish called it – Intramuros.

Other Filipinos, on seeing the Spanish were not invincible, rose up against the Spanish in an attempt to win back their independence – the Diego Silang and Palaris revolts in North Luzon.

At the end of the 7 Years War, Britain agreed to return the Philippines back to Spain. However, the brief occupation did influence Britain’s future, from simple to complex ways.

Famous products

First, the British brought back coarse brown paper made from the husks and straw of rice plants. Ah yes – Manila Paper envelopes.

They also discovered a rope made from a plant that was not affected by salt water. In the age of sail, this was essential to keep British dominance in the sea. This was Manila hemp or abaca.

They were also reminded that many areas of Southeast Asia were not controlled by their other competitor powers. Britain subsequently established colonies in Malaya and also seized control of the seaborne trade coming from South China.

In the end, the East India Company found a way around the restrictions the Spanish put on trade between the other colonial powers and its colonies.

The company decided to hire ships and crews from India so they could travel from India to Manila. The ships left India laden with cotton goods from British controlled factories, as well as iron. These were traded in Manila for Manila hemp, raw sugar, Chinese silk and porcelain as well as silver dollars from the South American mines at Potosi in Peru.

This trade flourished after the British Occupation of Manila until 1855, and is known by colonial historians from both Britain and the Philippines the “English Country trade.”

When the Bourbon dynasty assumed the Spanish throne in 1855, the new king allowed trade between Spanish colonies and other foreign nations. Thus Britain, in time, became the country with the biggest trade and commercial interests in the Philippines.

New technology

One of the most important persons involved in this new economic relationship was the British Vice Consul Nicholas Loney. Loney saw the potential in developing the sugar industry in the Philippines, and helped bring investments and steam technology for sugar plantations in Central Philippines.

Soon British steam engines powered the sugar mills, and trains moved sugar cane to the mills and raw sugar to piers built in the Victorian style. The first railway in the Philippines which ran from Manila to Dagupan City was built by the British – the Manila Railroad Company Ltd based in London.

British companies soon established offices in Manila. British ships would now routinely dock in Manila and transport Manila hemp, sugar, rum and tobacco. Other companies won contracts to that brought some of the most advanced Victorian era technology to the Philippines.

For example, the Eastern Extension China and Australasia Telegraph Company (which evolved into Cable and Wireless) won the contract to lay submarine telegraph cables that connected Manila to Hong Kong, and to the rest of the world.

The Rizal connection

Later, more submarine cables would be laid to connect Manila to the other cities in the Philippines that were growing as a result of foreign trade: Iloilo, Cebu and Bacolod. A British company also won the contract to build and run the first telephone exchange in Manila.

There were also stories of individuals that show the ties between British and Filipino people. One result of the Manila railways was that one of the engineers of the project wound up marrying the childhood sweetheart of the man who would later become the Philippines’ national hero: Dr Jose Rizal.

In the 1880s, Rizal was in Europe, pursuing his studies and later joined the reform and nationalist movement in Madrid. It was in London that he annotated Antonio de Morga’s Succesos de los Islas Filipinas, and established the tradition of Philippine history being written by Filipinos.

He also completed the first of his two novels that inspired Filipinos to later fight for independence from Spain: Noli Me Tangere.

Rizal would not have become the national hero if he had married his fiance, Nellie Boustead, whose father had cotton mills in Manchester. Neither Rizal or Boustead wanted to convert to the other’s faith and so the relationship ended. Rizal would return to Manila, and the rest is history.

Expanding interests

Continued British interest in the Philippines led to the creation of the British North Borneo Company, which successfully negotiated a lease of North Borneo from the Sultan of Sulu, one of the four sultanates in the Philippines.

Although the sultanates were now integrated into the Spanish Philippines, this did not prevent an agreement to lease land. It did however, plant the seeds of future tensions when the western colonial empires in the 20th century were dismantled.

North Borneo, or Sabah, was included in what would become Malaysia, but the Sultan of Sulu, through the Philippine government, still wanted his land back – an ongoing matter between Malaysia and the Philippines, and another example of the unintended impact of colonialism and imperialism.

Forged in combat

Another story was that a Scotsman, probably a former game keeper, trained a special group of Filipino marksmen. We don’t know his name, but the snipers he trained made a name for themselves in the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War: Los Tiradores del Muerte (‘The Dealers of Death’).

Other legendary officers in His Hispanic Majesty’s colonial Army in the Philippines were of Irish origins. The native peoples of the Zambales mountains were finally subdued and integrated into the Spanish empire through the military expedition led by a descendant of Hugh O’Donnell, the leader of the one of the four original Irish Catholic regiments that fought for the Spanish Crown.

During the Philippine Revolution, a truce was declared in December 1897, and the Philippine Revolutionary government, headed by Emilio Aguinaldo, was allowed to go into exile and was allowed by Her Majesty’s government to stay in Hong Kong.

Throughout the conflict and into the Philippine American War, Britain remained neutral and allowed Filipino exiles to stay.

Wartime allies

When the United States made the Philippines into its colony following their victory in the Philippine-American War in 1902, ties with Britain continued – but on a lesser scale.

These ties strengthened again in the Second World War, when Filipino, American and British forces fought as allies against the Japanese. These forces did not fight side by side, but did oppose a common enemy. I did hear from the Military Society of the Philippines that a few Filipinos did fight in Europe.

One Filipino pilot living in the US, First Officer Isidro Juan Paredes, saw action in Europe as part of the Air Transport Auxiliary of the British. Another Filipino pilot serving in the US Air Force, Col. Stanley Sabihon, flew 51 bombing missions over Europe. He was described as the “best pilot in the business” by his crew.

Ties that bind

There are more stories my dad tells of British-Philippine relations.

However, what remains in his memory is – as a young man who became part of the opposition to the Marcos dictatorship – how the British helped Filipinos in their fight to restore democracy.

He appreciated how Amnesty International was active in helping secure the release of many Filipino political prisoners. The Cooperative Bank refused to lend money to the Marcos regime, because the bank felt it would not be ethical to support a dictatorship.

The British government also allowed many Filipino exiles to take residence here in the UK. British trade unions, through the TUC, supported the Trade Union Congress of the Philippines (TUCP) to protect its members from harassment and intimidation from the forces of the Marcos regime.

Many British charities also supported counterpart charities involved in helping Filipinos, and put pressure on the Marcos regime to stop human rights violations.

Today, Filipinos are a visible part of British life, and Britain is still one of the largest trading partners and investors in the Philippines. These are ties that bind.