By Veronica Pedrosa

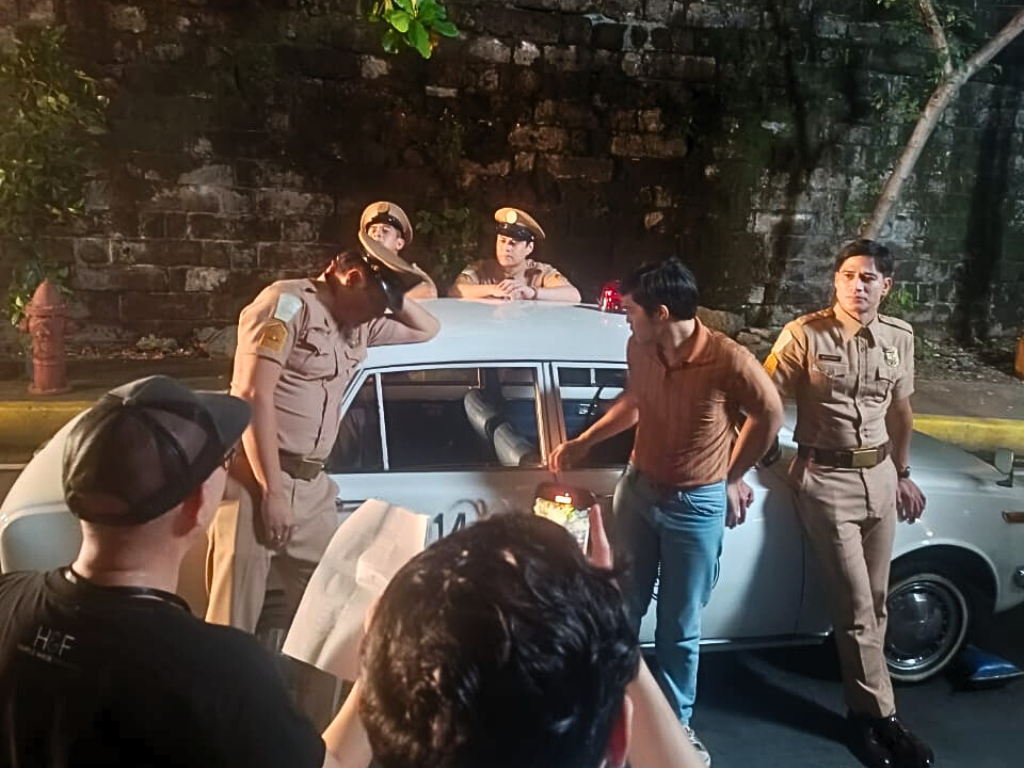

By the time “Manila’s Finest” reached Philippine cinemas last Christmas, it was an anomaly. A slow burn, character-driven film set in the late 1960s—years before Ferdinand Marcos formally declared martial law—it arrived in a commercial film landscape dominated by spectacle, comedy and easy sentiment.

And yet, against the odds, it seems to have found its audience.

Co-written and co-produced by filmmaker Moira Lang, “Manila’s Finest” has since picked up awards and strong word-of-mouth, praised for its restraint and emotional weight.

Rather than retelling history through an explicitly political lens, with speeches and slogans, the film inhabits the everyday lives of Manila police officers at a moment when the institutions meant to protect the public were quietly beginning to change.

For Lang, that approach is deliberate—and deeply personal.

From independent cinema to an unlikely Christmas release

Lang is no stranger to independent filmmaking. Her first producing credit, “The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros” (2005), became a landmark of Philippine queer cinema, screening at Sundance, Berlin and beyond.

This year, more than two decades on, it returns to the Berlinale as part of the Teddy Awards’ 40th anniversary retrospective—a reminder that Philippine art cinema has long been alive, if often working at the margins.

She later co-produced Lav Diaz’s “Norte, the End of History,” the four-hour epic inspired by Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” that cemented her reputation internationally. For many viewers outside the Philippines, Norte was a revelation: a film unafraid of long silences, moral ambiguity and class fracture.

That same sensibility runs through “Manila’s Finest,” even if the film’s origins were unexpectedly modest.

“It began with a Facebook post,” Lang recalls. “A friend living abroad wrote a long, intimate reflection about a policeman in late-1960s Manila—a tribute filled with anecdotes and quiet affection. The subject, it turned out, was his father, a member of the Manila Police Department, then popularly known as “Manila’s Finest.”

Reading it, Lang immediately saw cinematic potential. “I thought: this has to be a personal story,” she says. “But the bigger story is what’s happening around them that they don’t yet see.”

Manila as a testing ground

As Lang researched the period, a pattern emerged. Long before the official declaration of martial law in 1972, the signs were already there: curfews, protests, creeping militarisation, and the growing presence of the Metropolitan Command or METROCOM encroaching on civilian policing.

METROCOM was a specialized unit of the Philippine Constabulary created by President Ferdinand Marcos on July 14, 1967, through Executive Order No. 76.

“In a way, Manila became a testing ground,” she explains. “You could see how far the state could go. It was a microcosm of what was about to happen to the whole country.”

Crucially, “Manila’s Finest” never centres Marcos himself, or any of the powerful figures behind the scenes. Instead, the camera stays with the policemen—men who still believed they were serving their communities, who remembered a time when people felt warmth rather than fear when they saw a uniform.

“That’s what moved me,” Lang says. “A time when people still had affection for the police. And how that affection slowly erodes.”

The tragedy of the film lies in what the characters cannot yet recognise. The political shifts are there—in rumours, in absences, in offhand remarks—but by the time the changes become undeniable, they are already in place.

“At some point,” Lang says, “when you finally realise what’s happening, it’s already too late.”

Making the film—against the odds

From a producer’s standpoint, “Manila’s Finest” was a hard sell. A period piece. No obvious commercial hook. Too bleak to be a “feel-good” film, yet too grounded to sit comfortably as art house fare.

Even Lang was sceptical when MediaQuest, the production company backing the film, suggested submitting it to the Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF)—a Christmas festival synonymous with mass-appeal releases.

“I told them, ‘Are you crazy?’” she laughs. “It’s not a Christmas movie.”

What changed everything was the involvement of star actor Piolo Pascual, who responded strongly to the script and agreed to attach his name to the project. With deadlines looming, Lang and her collaborators—including veteran writer Michiko Yamamoto—rushed to complete the screenplay in a matter of weeks.

Against expectations, the film was selected.

It looks and sounds terrific. The art direction, production design and musical score wonderfully evoke a bygone era with an affectionate but open-eyed nostalgia. Lang shared the deeply romantic playlist of kundimans from the era with me when I commented on the careful curation of music in the film.

It reclaims “Dahil Sa Iyo [Because Of You],” from the fatigue of overuse in Imelda Marcos’ political rallies back in the velvet tones of Diomedes Maturan. Leopoldo Silos’ “Filipino Offbeat Cha cha cha” is another perfectly placed track in the movie that lifts and colors the emotional narrative and somehow gives it back to ordinary people who lived through those turbulent years.

The film’s initial reception was mixed. Opening on Christmas Day, audiences distracted by holidays and reunions were unsure what to make of it. But as the weeks passed, something shifted. The film stayed in cinemas longer than expected, buoyed by word-of-mouth and a growing sense that it was speaking—quietly but clearly—to the present moment.

Lang remembers leaving early screenings unsure how audiences would respond. “That first week was hard,” she admits.

A film that resonates beyond the Philippines

Watching “Manila’s Finest” today, it’s hard not to draw parallels beyond Philippine history. Lang herself notes how the film resonates amid the global return of “strongman” politics—from the Philippines to the US and Europe.

“What’s happening in the system that’s supposed to protect the public,” she asks, “that turns it into something people fear?”

For Filipinos in the diaspora—particularly second- and third-generation viewers—the film offers a way back into history without didacticism. It invites reflection rather than demanding allegiance.

Lang is especially pleased when viewers catch small historical references, such as the subtle nod to Liliosa Hilao, the student activist whose death in custody became a turning point in opposition to the Marcos regime. These details, she says, are acts of remembrance.

“They honour the people of that time.”

What comes next

For now, Manila’s Finest has screened primarily in the Philippines. Lang and her team are submitting it to international festivals, hoping to premiere the film abroad later this year. The goal is clear: to bring the film to Filipinos overseas—and to non-Filipino audiences curious to understand the country beyond headlines.

“It’s not just about 1971,” Lang says. “It’s about how erosion happens—slowly, quietly—until one day everything is different.”

For viewers willing to sit with its silences, “Manila’s Finest” offers something increasingly rare: a film that trusts its audience to feel, remember and think.

About the Author

Veronica Pedrosa

Veronica Pedrosa is an award-winning international journalist with more than 20 years of frontline experience. She has reported, anchored and produced for the world’s leading broadcasters, including Al Jazeera English, CNN International and BBC World News.

Her career also spans humanitarian advocacy and strategic communications, with extensive field experience, giving her deep insight into crisis communications, strategic messaging and the ethics of storytelling in emergency contexts.