Leo Christian V. Lauzon

This year marks nine years since super Typhoon Haiyan, locally known as Yolanda, brought unparalleled destruction to the lives of the people of Eastern Visayas. On 8th November (7th Nov UK time) 2013, Haiyan struck central Philippines, leaving some 8,000 people dead and 29,000 people injured, the majority of them from Leyte province. A total of 16 million people were affected, four million of them were displaced.

In what may be considered as pa-siyam, the Filipino tradition of praying nine consecutive days for the dead, this year’s anniversary marks the end of a nine-year commemoration for those whose lives were taken by Haiyan. Yet, for most of us survivors who lost loved ones on that fateful day, the closure remains something we have to decide for ourselves as succeeding typhoons that brought similar magnitude of devastation and the continuing loss of lives in its wake continue to remind us of our ordeal and the trauma that seems to have no end.

When the typhoon struck that day, I thought it was another ordinary typhoon we are used to encountering on a regular basis. Tacloban City, Leyte, is located in the eastern part of the Philippines and serves as the capital of the Eastern Visayas region. Facing the Pacific Ocean, we are directly on the path of the typhoons that develop from the vastness of the Pacific. Growing up, I was used to seeing family members and neighbours being up on the roofs fixing any leaks while a storm rages. I remember one particular instance when we were under typhoon signal number 3 but the sun was shining. Nothing prepared me for Haiyan’s force, considered as one of the world’s strongest typhoons which recorded 315 kilometres per hour of wind speed at landfall. Images of Tacloban’s total devastation shocked the global community as help started to pour into affected areas.

For the first time in my life, I was leaving Tacloban not to represent my place of birth and the Philippines to the international stage but because I was internally displaced. I slept on the porch of my uncle’s house as there were many of us who took shelter in his home, desperate for a space to sleep and rest even when its roof needed to be repaired. I developed an infection in my feet from wading in the murky floodwaters brought by the storm surge. My feet required a minor operation and antibiotics before they completely healed.

It took me five days before I was able to communicate to worried and anxious loved ones and friends that my family and I are alive. However, my Aunt Rosa and cousin Nida were not able to make it to safety. They remain missing to this day.

Nine years have passed and while there are only a few physical reminders of the harrowing tragedy that befell our city, the emotional scars left by Haiyan are etched in every heart and mind of the people of Tacloban.

As a Haiyan survivor and a humanitarian worker, allow me to share some reflections as we commemorate the anniversary of the strongest typhoon that struck the Philippines:

1. We need to teach local history.

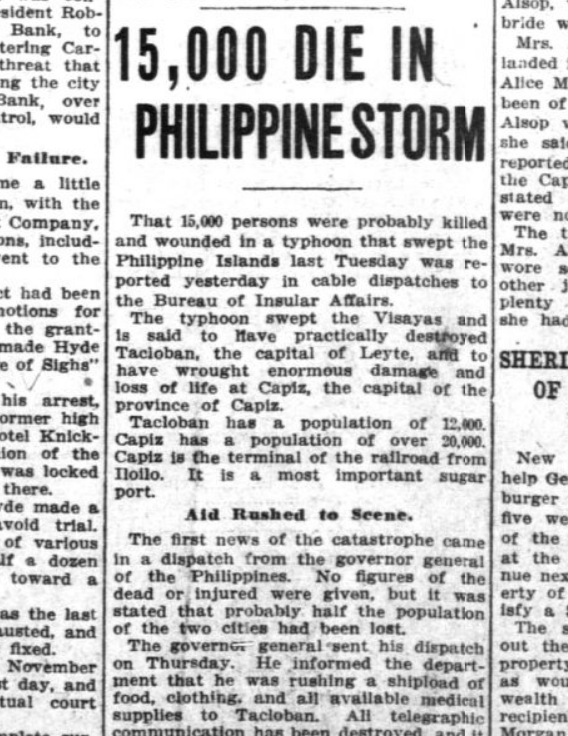

There were at least three super typhoons that devastated Eastern Visayas prior to Haiyan. In 1991, Tropical storm Thelma (Uring) caused a 22-inch flash flood in Ormoc and the rest of Leyte killing at least 5,000. Almost 80 years before that in 1912, a tropical storm with similar intensity as Haiyan, ravaged the towns of Tacloban and Capiz, with the death toll estimated at around 15,000. Earlier still in 1897, a “tidal wave” struck Tacloban “with great fury,” leaving between 1,300 to 6,000 people dead.Yet, these significant events are not part of our local history. It was only after Haiyan that we came to know how Leyte had been previously ravaged by super typhoons a century ago.

This historical information could have warned the people of Tacloban that disasters such as these could potentially strike again in the present. Teaching local history and setting up museums will enable us to learn more about our past and draw lessons that could help us be better prepared for upcoming disasters. The continued loss of lives in the succeeding typhoons after Haiyan that hit Eastern Visayas is an indicator that we have not learned our lessons.

2. Building resilience starts with disaster preparedness.

Preparedness should be consistently done and imparted to individuals and families. For a region that is vulnerable to almost all forms of disasters, except perhaps for volcanic eruption, there must be an aggressive and massive information dissemination and capability building. Women and children must be equipped with life skills such as swimming and they should be part of the decision-making process whenever the family decides to evacuate among other crucial decisions that are mostly decided by the men in the family.

3. Good governance is key.

Nine years after Haiyan, there are still houses that need to be constructed in selected resettlement sites in Tacloban. Meanwhile, installing water supply for these resettlement areas which had allocated funds is years behind schedule.

A month ago, I was in one of the resettlement sites when I noticed that there are houses with only the foundation in place. But I was informed by those who are living there that these unfinished houses had already been raffled to beneficiaries who were allegedly told by authorities to follow-up with the contractor to finish the housing construction. As to confirming the identities of bodies recovered in the aftermath of the storm nine years ago, some families are still waiting for DNA testing to be done because of the apparent lack of reagents. This is a disservice to Haiyan survivors.

Nine years after the storm, most of us are back on our feet with our jobs and our homes but let us not forget those who have been left behind: the homeless, waterless, and voiceless. We have to advocate on behalf of those who are not being heard. As the newly appointed co-chairperson of the Regional Development Council in Eastern Visayas, I urge for the continued monitoring of post-Haiyan projects that are yet to be finished.

Our fast recovery was a result of a global effort coupled with national and local government cooperation and the resilient spirit of the people of Eastern Visayas. From grateful people in the eastern part of the Philippines, we say “Damo nga salamat” to all those who helped us in our hour of need. We will pay it forward by helping fellow Filipinos affected by the recent disasters and ensuring zero casualties in the near future.

Top photo credit: Liezel Longboan

About the author:

Leo Christian V. Lauzon is an independent gender and development consultant and president of Kabataan San Sidlangan, Inc. He served as the Chairperson of the Regional Gender and Development Committee (RGADC) VIII – Eastern Visayas from 2016-2019 and at present, the Private Sector Representative of Persons with Special Concerns at the Regional Development Council (RDC) VIII, the first young person to sit in the highest policy-making body of Region VIII. He was recently appointed by President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. as RDC VIII co-chairperson. He served as a gender specialist and humanitarian worker during the Typhoon Yolanda emergency response, the Marawi siege recovery and rehabilitation, and Typhoon Odette response.