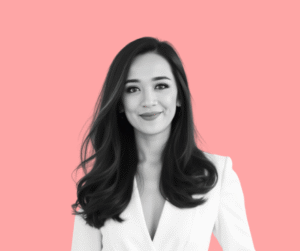

By Mari-An Santos

Four young Filipino nurses have been speaking to Mari-An Santos about their experiences of working in NHS hospital Covid-19 wards and in intensive therapy units (ITUs). Their ages range between 27 and 31 and most of them have been in the UK for less than 5 years. As the UK’s coronavirus death toll passes 50,000, we would like to share their stories of working in the frontlines.

Mae Cabanit tells her story in third piece for this series.

Mae Cabanit, 29, is an ITU nurse in London. She had previously worked as an ICU nurse in Cebu for more than four years. At the end of February, when there was rising concern over Covid-19 cases, she steeled herself. “I was telling myself: You’ve been through worse! The cases of tuberculosis that we had to deal with in the Philippines was worse. Reusing PPEs and masks–I’m used to that. I thought I was prepared for this because of what I went through in the Philippines.”

In February, Cabanit had just come back from a visit to the Philippines following a family emergency, and was getting used to working again when cases of Covid-19 started in the UK. To make matters worse, her partner had gone ahead to Peru where they were to meet in a couple of weeks for a holiday. They were kept separate during the entire period of lockdown.

Alone yet trying to be focused

“I felt sorry for the patients because they died alone. Everyone was struggling… The patients were from any age group–not just old people–about the same age or younger than me.

Though she has vast experience in ITU, Cabanit characterises the first wave as “The worst time in my career because there were so many people dying, and they were dying alone.

“I had to manage my emotions. I told myself: ‘I cannot break down during my shift because there are so many things that still need to be done. So I need to focus.'”

“I had to manage my emotions. I told myself: ‘I cannot break down during my shift because there are so many things that still need to be done. So I need to focus.’ I would go home and let all my feelings out, just cry so I could release all my emotions, all the stress. I was all alone,” she confesses. “But during that peak, I would offer to take extra shifts. I would rather work than be alone at home, and be worrying about my family.”

‘Very tired, super tired’

“We only had two-hour breaks during each shift–one shift is 12 hours–and that was the only time you could drink, eat, go to the toilet. You cannot drink a lot of water, because you would need to go to the toilet, and you cannot go when you are wearing your PPE. So you’re dehydrated the whole shift until you get home.

In an ideal setting, one person is assigned to each room, but because we were understaffed and overwhelmed with the number of patients, we had to double our load. We were overworked, very tired, super tired.”

“At the height of the first wave in April, I thought: I wish I was still in the Philippines, then I could be helping my fellow Filipinos during this pandemic,” Cabanit says. “But then, I’ve been hearing a lot of stories from my friends who are still in Cebu. For example, some of them have to ride bikes between home and work because the jeepneys [the main type of public transportation in the Philippines] will not let them on. I don’t think they would appreciate my efforts in the Philippines.”

Frustration at people not taking precautions

Thinking about the second lockdown in England, she says candidly: “I am relieved because it will help health care workers manage the second wave a lot better. We have already been given notice that if other hospitals in our trust receive more Covid-19 patients, we will be redeployed.”

They don’t see the struggle that we see. They only see the numbers. They don’t see the patients taking their last breaths.

Still, during her daily commute, Cabanit would observe people who were not wearing masks, not following precautions. “It makes me feel very angry. I understand, they don’t see the struggle that we see. They only see the numbers. They don’t see the patients taking their last breaths.

Unless they see the reality, they won’t believe. I want to get angry, to rant, but it’s pointless, a waste of energy…” What does she do instead? “Just pray to help strengthen you. If people say racist things, it’s not directed towards you. They are just frustrated. You should not take it too personally.”

Mari-An Santos is a freelance writer based in Manila. She recently finished a Joint Master’s degree in Women and Gender Studies from the University of Granada (Spain) and University of Lodz (Poland). Her thesis tackled Emotional Geographies of Ageing Filipina Migrant Workers in Valencia, Spain.