Carla Montemayor

What makes for “horror” in a horror film? Typically, it’s a monster or supernatural creature, agonising methods to kill and die, malevolent magic beyond human control. In Raging Grace (Paris Zarcilla, 2023), the horrific element is in the hidden yet pervasive dehumanisation of migrants. The exploitation, the casual humiliations they are subjected to, the literal theft of agency and space to lead full lives.

With a tenth of our population dispersed around the world, Filipinos are familiar with these tropes. The film’s main characters are a cleaner, Joy (Max Eigenmann), and her daughter Grace (Jaeden Paige Boadilla). Joy works on her hands and knees to provide for Grace, and is forced to seek dodgy solutions to their precarious living conditions as undocumented migrants. She chances upon a seemingly ideal job looking after a wealthy, comatose man in a cavernous old mansion but senses quickly that something is not quite right.

As with other “horror” films and thrillers, my favourite thing is to see if and how the protagonist survives. Is she brave and resourceful enough to defeat the diabolical forces out to get her and her loved ones? This, to me, is the appeal of this particular genre (or perhaps of all film and literature): How does one love and thrive in a world determined to crush us?

Social realism in Philippine cinema

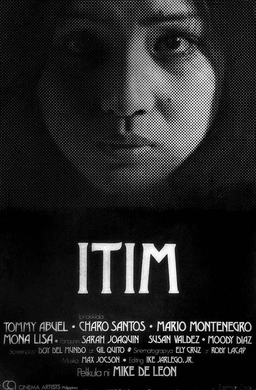

I grew up on social realist films produced during what is referred to as the second Golden Age of Philippine cinema. Film making giants such as Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal were among those who made explicitly political films under the Marcos dictatorship. These were powerful films showing poverty, violence and injustice in all its technicolour squalor. My favourite from this era is Mike de Leon, who explored various forms, including two horror-thriller films – Itim (The Rites of May, 1976) and Kisapmata (In the Blink of an Eye, 1981) – both exploring themes of tyranny and coercive control in the context of small towns and families.

I miss those films, in all honesty. I rejoice every time a visiting friend is kind enough to haul DVDs of the latest indie films from Manila but there is an indelible mark left by films watched covertly as a teenager living under a dictatorship. These days I favour comedies/satire and loved the Ang Babae sa Septic Tank trilogy (The Woman in the Septic Tank, directed by Marlon Rivera and written by Chris Martinez) – a send-up of Philippine cinema and showbusiness. I admire Jerrold Tarog, though more for the romantic drama Sana Dati (2013) rather than the series of historical films kicked off by Heneral Luna (2015).

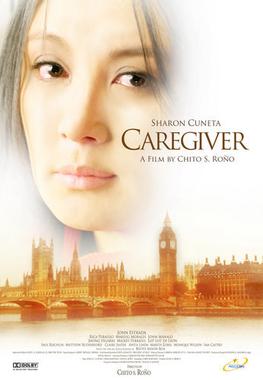

With the exponential growth in Filipino migration during the same period and my own journey as a migrant over nearly two decades in the UK, I find myself seeking films centering migrants. The first film I remember seeing is Napakasakit, Kuya Eddie (directed Lino Brocka, written by Jose Javier Reyes, 1986). Set in the Philippines, it focused on fractured family life after the father goes to work overseas. In 1996, the Flor Contemplacion Story (directed by Joel Lamangan, written by Bonifacio Ilagan and Ricky Lee ) came out after the execution of the eponymous protagonist accused of murdering her fellow domestic worker and the child they looked after in Singapore. The last I saw was Caregiver (directed by Chito Roño, written by Chris Martinez, 2008), which was about a schoolteacher who leaves her job and child to join her husband and work as a carer in London.

All three can be classed as melodramas, all written by eminent Filipino screenwriters and directed by acclaimed Filipino directors, featuring huge Filipino movie stars. All were hits with Filipino audiences, where the impact of absent family members is acutely felt, and the idealised status of overseas workers as breadwinners and “new heroes” permeates the national consciousness.

Migrants telling the stories of their lives

I have since been preoccupied with this question: How do migrants tell our stories in the societies we actually live in? How do we speak about ourselves to each other and to the peoples with whom we co-exist? Raging Grace provides key insights: One, that we need to shape the narratives ourselves and rise out of the crevices in the landscapes we inhabit. Two, we find new forms to depict our humanity.

I will not belabour the first point about owning our stories – “representation” is a straightforward issue in my mind. Invisibility and expendability in economic and political spaces means invisibility and expendability in the cultural sphere. Filipino migrants are estimated to be around 250,000 (a contentious figure that may or may not include next-generation Filipinos and those with British citizenship) but we have an outsized presence because of Filipino nurses, carers and other health professionals in the NHS. This is a tiny figure compared to the Filipino American population. Filipinos spent “300 years in the convent and 50 years in Hollywood”, as the cliché goes. Cultural sensibilities in the homeland and among most Filipinos skews towards America while British Filipinos struggle with being seen and heard in a specific socio-cultural context.

Raging Grace director Paris Zarcilla, whose Filipino parents were domestic and care workers themselves, acknowledges that he was raised to keep his head down; to do his best but not rock the boat. He knows that this was part of a survival strategy but laments how it made him lose his language and his pride in his origins. He is aware of the caricatures attached to Filipinos, as evidenced in the films British characters’ breezy assumptions about “the help”: a “happy people”, “obedient”, docile and loyal. Thus he subverts these with his portrayal of Joy, who defies the complicity required by her employers and clings to her moral compass despite her desperation; of Grace, who is wilful, mischievous and resists the unfairness she is required to silently endure. We need to look to migrants to articulate our lived experience.

Which brings us to the second point about form. Zarcilla, in his debut feature film, chose “horror” spiked with humour and absurdism. In the Q&A after the Raging Grace screening at Rio Cinema, he said that the treatment of migrant workers in the UK is in itself “horrific” and thus lends itself to this treatment. To my mind, this is a good choice of vehicle to illuminate the everyday realities and the systemic issues migrant workers face, without being didactic. The facts are known, the truths need to be articulated.

This is an important film and a massive forward movement in migrant cinema. Go see it.

About the author

Carla Montemayor is a writer and movie fan. She won a London Writers Award in 2021 and was a fellow of the London Library’s Emerging Writers Programme for 2022-23. She is working on a book about the storytelling tradition among the women in her family.